Icelandic Language | Viking Heritage, Development & Today

When you have a nation of 360.000 people it is definitely not a given that its people will have their own language. Most would probably guess the opposite. Therefore, does the fact that Icelanders have a completely unique language, called Icelandic, come as quite the surprise to many people.

This language – spoken by oh so few – is undoubtedly the most similar to the old Viking Language. The reason, many say, is the confinement from complete isolation endured by the settlement well into the 20th century. With no outside influence, the language would only have developed within the very distinct borders of the island but in truth, it didn’t change much at all.

Icelandic is the official language of Iceland. You will hear it everywhere you go. It is taught in schools, used in debates in parliament, regulated through news reporting and can be read in books and magazines. Television is not dubbed but nothing is aired without subtitles or some form of translations. But before we start talking about modern times, let’s dig a little deeper and find out about Icelandic’s origin!

The Origin of the Icelandic Language

Icelandic is a West-Nordic, Indo-European and Germanic language. Its roots can be traced back to the oldest Nordic language which was spoken in Scandinavia between 200 and 800 A.D.. During the Viking age, year 793 A.D. to 1066 the Nordic language split into East and West. East-Nordic later developed to Danish and Swedish and the Western part evolved to Norwegian, Faroese (spoken in the Faroe Islands), and some centuries later, Icelandic. Most of the Icelandic settlers came from West-Norway which explains the connection.

Therefore, in the early days, Norwegian and Icelandic were almost the same but around the year 1400, the languages had changed enough to be recognized as two different tongues. The differences would continue to grow throughout the years.

Further influence on the Icelandic language

What might come as a surprise is that a substantial part of Iceland’s settlers were actually from Ireland, Scotland and Britain but their linguistic influence seems to have been minimal. It can mostly be seen through names of people and places although the odd word here and there has possible linkage.

How do Icelanders preserve their Language?

Icelanders go to great lengths to preserve their language. Unlike their neighbors, Icelanders will not take up the English words for new things that come along like a computer or a helicopter. What they will do instead is look into the meaning, or purpose of this new item and see if they can’t find a good old Icelandic word describing it in some ways. When computers started to get popular globally Icelanders decided this was one of those word-making moments. After careful consideration, the words tala (number) and völva (a predictor of event/things) were picked, combined and sculpted into the word tölva. And, as unlikely as it may seem, this actually worked. Tölva is still today the only word that we use for a computer and has even reused it for things like spjaldtölva (iPad or tablet) spjald meaning card refers to the actual thinness of the hardware.

Another way they preserve the language is with their naming committee. An academic committee made up by scholars and lawyers to decide whether new names should be allowed or not. Don’t get me wrong. There are thousands of options for you to use when naming your child. But, if you want to name your child something that has never been used before in Iceland. You’ll have to go through the committee.

Find out more about Icelandic Names

A third example of how Icelanders maintain their language skills is through learning about Icelandic sagas. The high school curriculum has teenagers reading the old literature, in its original form, and pupils are tested on their knowledge of this unique Viking heritage.

Icelandic and Technology

The Icelandic government recently decided to allocate 450 million krónur or 4.48 million USD every year for the next five years to raise capital for a special language technology fund. The fund is meant to help produce open-source materials that developers can then use to create semantic technology. This could, for example, led to popular apps having an Icelandic language option. Something that we have never seen with the bigger apps like WhatsApp or Instagram.

Despite this, radical action is something that the government sees as an essential step in order to modernize the language and keep it afloat. This is in all likelihood an answer to risen concerns all around the world, which gained attention with the Guardian’s article “Icelandic Language battles threat of digital extinction“. With immense numbers of people using social media and other technologies for most of their communications, Iceland might lose the fight for existence if they don’t get with it. So, who knows maybe one day we’ll have an Icelandic Alexa.

Is Icelandic hard to learn?

The Icelandic language is famous for being exceptionally hard to learn, with letters such as æ,ö,ð and þ it almost comes off as cryptic at times. The way you write and pronounce the words are miles apart. And, just when you think you have gotten the hang of it you’ll find about seven exceptions to this grammar rule.

Getting to know the Icelandic language might feel like stepping into a linguistic jungle but trust me when I say it does get better. As soon as you start to understand some of it, a much better grasp will soon follow. This mainly has to do with the fact that the Icelandic language is very see-through. A word like regnhlíf (e. umbrella) is literally made up from regn (rain) and hlíf (coverage). Other examples are ísskápur (refrigerator) but ís means ice and skápur means closet and dýragarður (zoo) but dýr means animals and garður a garden. So, if you use your common sense and do a little linguistic math you might just start to understand all those big words. After all, they are usually just made up of many other smaller ones.

To sum it up

Yes, Icelandic is very hard to learn. We have numerous ways to change each word and will, for example, use i and y with no pronunciation difference. For instance, if you write kirkja, it means church but if you write kyrkja it means to strangle. Even though there is no difference in the way these two words are pronounced. It is all about the context!

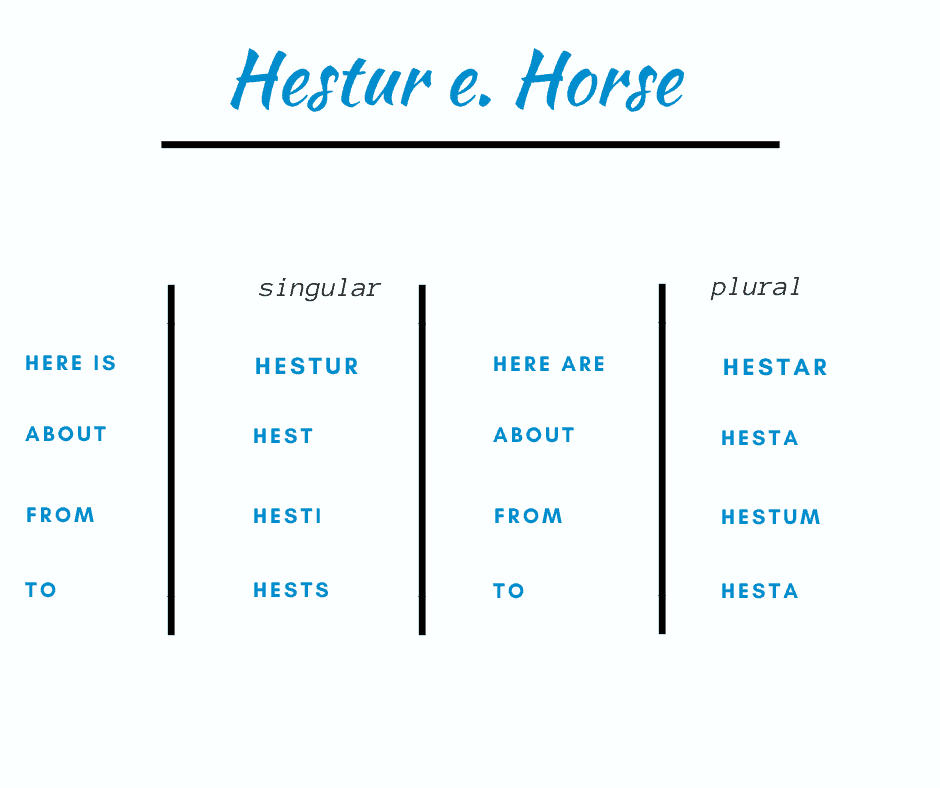

Another way we have found ways to complicate the language are tenses and functions. Here I will use the word hestur, the Icelandic word for horse.

Funny Icelandic Words that don’t exist in English

Jæja

Now, this is a hard one to explain. It can main so many different things. The closest in any other language I have found is Allora in Italian but so far, nothing in English. It can for example mean:

- Let’s go.

- This party is over.

- You have overstayed your welcome.

- Lunch is over.

- This topic is getting out of hand.

- I don’t agree with you but can’t be bothered to argue.

- Stop talking.

- Moving on.

- But also, jæja, I can’t think of more. But, there are endless ways to use jæja which is pronounced a bit like yaiya.

Trúnó

An intense conversation usually one-on-one where people reveal deep emotions or secrets. This happens more frequently when people have been drinking. You can go on a trúnó with anyone, from a best-friend to a stranger in a club bathroom.

Mæðgin | Mæðgur

Mæðgin is mother and son but mæðgur is mother and daughter. These words are very useful and are commonly used in everyday life.

Feðgin | Feðgar

The same goes for feðgin but this means father and daughter. Feðgar on the other hand is father and son together in one. If you want to start using these words keep in mind that ð is pronounced the.

Frænka/Frændi

These words are some of the ones that I miss the most when speaking English. They simplify the word relation between a specific kind of relativity and just someone you are related to. Let me explain: If I say that this person is my frændi, the only real information I have given you is that he is male and he is related to me. Frændi can be a third-cousin or your uncle. They will all be given the same clarification. The same goes for frænka, but this time it’s for females.

So, frændi, is anyone male who is related to you or the person you speak of and frænka is anyone female who is related to you or the person you speak of. Now please let’s find a synonym in English!

Where does the Icelandic Language stand Today?

The Icelandic language is still the number one language spoken in Iceland. It is without a doubt the official and un-official language of Iceland. When you look to the younger generation you see a lot of slang but Icelandic has not considered any less cool than it was before. This can perhaps can best be seen through its usage by Icelandic rappers and singers. Most songs being produced in Iceland and that become popular are in Icelandic.

This would most likely not be the case if the language would walk a precarious path. Artists not only use the language but take pride in speaking it well and having a rich vocabulary.

The same goes for TV or films being made in Iceland. Those produced by Icelandic companies are made in Icelandic and this does not change even with a rising fan base abroad. Let’s take Ofaerd (Trapped) as an example, which was on BBC’s list of things to watch in 2019. The series is all in Icelandic and people love it. Therefore I don’t see a swift change in that anytime soon.

On a more negative note…

However, it has been shown that literacy among Icelandic children is falling at a rapid scale. As well as a shrunk vocabulary. This is something that the older generation worries about especially with books becoming less popular and everything relating to Artificial Intelligence taking over. Icelanders link their identity strongly through their language so it is hard to say what this might mean for the nation-state. Hitherto we have not worried too greatly but we can see it in the amounts of government money being ministered to this category that this might all be changing.

Icelandic to English the Essential Travel Dictionary

Good Day – Góðan daginn (used in the morning and until about 6 pm)

Beautiful – Fallegt

Delicious – Ljufengt

Where is x – Hvar er …

I don’t speak Icelandic – Ég tala ekki Islensku

Do you speak English? – Talar þu Ensku?

Good Evening – Góða kvöldið

One beer please – Einn bjór takk

(When thanking for a meal, tour, or a ride) – Takk fyrir mig

Good Night – Góða nótt

How do I get to … – Hvernig kemst eg til …

I love this – Ég elska þetta